Sussex Kelp Recovery Project

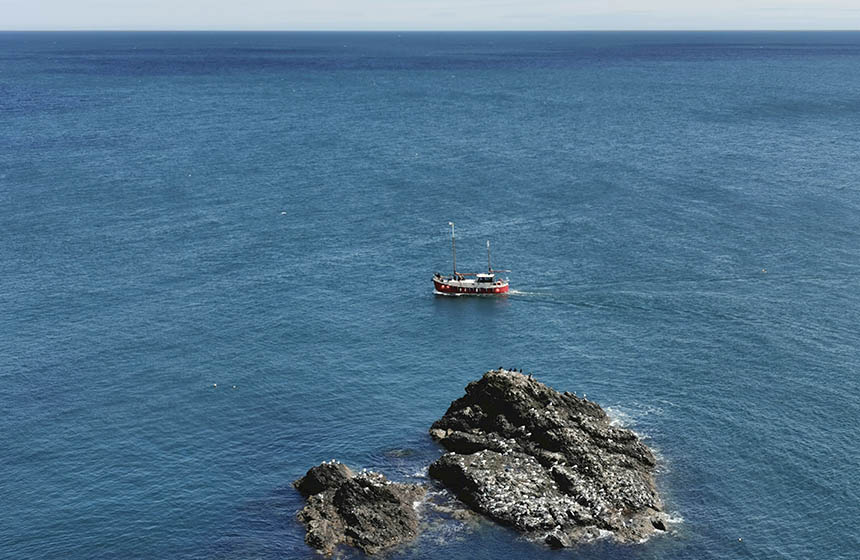

The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project has been established to monitor, assess, and assist the natural recovery of kelp forests on the West Sussex Coastline, following a public campaign that led to landmark legislation banning trawling in the area.

Nature-based intervention:

The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project (SKRP) commenced in March 2021, after a long campaign led to the implementation of the Sussex Nearshore Trawling Byelaw to prevent further damage to the remaining kelp beds. This legislation bans heavy trawling throughout the year to protect 304 km2 of kelp forests along the Sussex coastline, and the marine life they support.

While most kelp projects globally use active planting, the SKRP is exploring whether it is possible to ‘rewild’ the seas by supporting and monitoring the natural recovery of the kelp following the ban on trawling. A key feature of the project is that they adopt a holistic approach, examining both socioeconomic and ecological outcomes. This is supported by thorough monitoring using various cutting-edge techniques. Although the overall goal is for nature-led recovery in the protected site, SKRP continuously assesses whether active restoration would also be beneficial – they report that additional planting and seeding may become useful in the future. They also work to identify and manage potential barriers to recovery, with a large focus on sedimentation processes, which are identified as a key issue by various stakeholders.

Community engagement and education about the importance of kelp ecologically, commercially and recreationally are also major elements of the intervention. The SKRP have worked with universities and local schools, and have acquired a large social media presence. They have also hosted a Kelp Summit, furthering their goal of reaching a global audience.

The Sussex Wildlife Trust trialled the application of the IUCN Global Standard for NbS to inform and develop the design of the SKRP, acting as one of initial projects in the UK piloting the Standard’s self-assessment tool. The project is also part of the wider Weald to Waves initiative, which aims to establish a 100 mile nature recovery corridor across Sussex to connect the fragmented landscape and link it to the sea.

Overview of context:

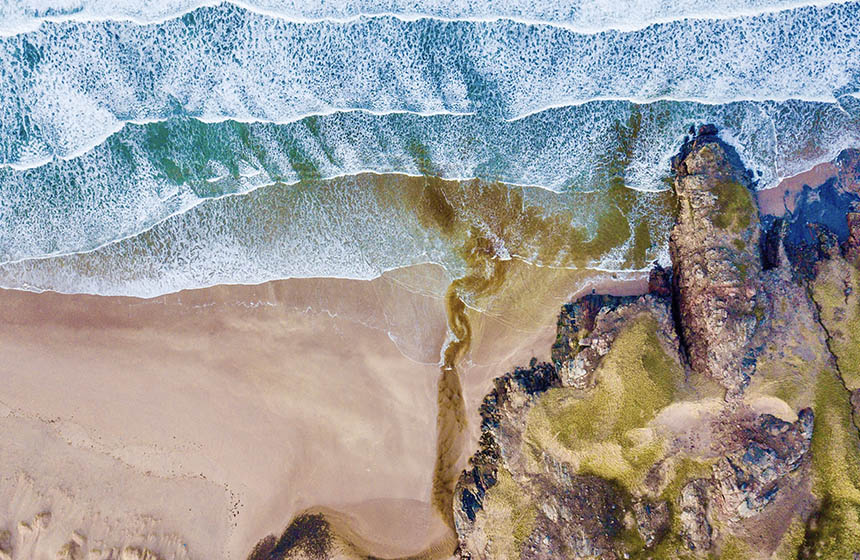

Kelp are large brown seaweeds (algae) commonly found in cool, rocky waters close to the shore. Thriving at high densities, they form so-called ‘kelp forests,’ which are some of the most biodiverse marine environments on the planet. Back in the 1970’s, the kelp forests along the Sussex Coast were vast and teemed with life. The once 170 km2 kelp forest supported numerous species including the European Lobster and Sea Bass. Since then however, the devastation of the Great Storm of 1987 alongside extensive fishing using heavy trawler nets has resulted in the disappearance of 97% of the kelp and the marine life it supported. Under growing concern, the ‘Help our Kelp’ campaign was set up which worked alongside the Sussex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority to pass the byelaw. This eventually evolved into the SKRP which oversees the recovery today.

Case effectiveness on

Climate change

Like all photosynthetic organisms, kelp absorbs carbon dioxide and converts it into organic carbon. When the kelp rots, some of the carbon returns to the atmosphere but some sinks into the sediment on the seafloor and is buried, where due to the lack of oxygen it can store carbon for over 100 years. However, it is very difficult to measure burial and sequestration rates as these are highly dependent on currents and seabed topography, and so the project has not yet quantified carbon storage.

As well as having direct carbon sequestration potential, kelp is thought to ‘animate the carbon cycle’ by providing the foundation for a healthy ecosystem of marine life, which is better at capturing and storing carbon. To help inform the value of kelp as a blue carbon store, the rate of carbon draw-down and storage in sediments is being analysed from 24 sediment cores taken from the seabed.

Kelp beds can serve as natural coastal defences, absorbing energy from waves and storm surges. Under climate change, the severity and frequency of storm surges are expected to increase, therefore, the presence of kelp beds is crucial in enhancing resilience to climate change in these areas. The multi-dimensional habitats kelp provides also support many vertebrate and invertebrate species including commercial fish stocks, which upon recovery, could further contribute to climate resilience through food security. However, given the project is in its infancy, no evidence has yet been gathered on these outcomes.

Ecosystem health

Ecological effect: MixedNo major kelp recovery has yet been observed in the protected area as the project has only been running since 2021, but more short-algal cover has been reported. A large fluctuation in Bootlace Weed (Chorda filum) has also been recorded, which is a key indicator of early signs of recovery. Despite these positive signs, measures of overall biodiversity have remained constant since the legislation preventing trawling was passed. There was also no significant difference between species richness inside and outside the protected area found thus far. Fewer invertebrate species were recorded in 2022 (14) compared with 2021 (24), and a reduction in the number of herbivores has also been reported. The latter seemingly negative outcome may suggest a lack of decaying vegetation to feed on.

Socioeconomic outcomes

Citizen science and young researchers have been playing a key part in the project; for instance, 16 university degree students have carried out their research projects on the kelp. Questionnaires were used to gather information on local fishers’ individual practices, income, and well-being. Respondents using static gear, on average, had a higher job and income satisfaction since the byelaw passed. Lower levels of stress were also reported. The SKRP has reached a global audience through a diversity of outreach events, which has boosted tourism in the area.

Governance

Local participation in Governance: ActiveThe initiation of the byelaw followed investigations led by the Sussex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (Sussex IFCA) and local universities in partnership with the Sussex Wildlife Trust. The Sussex Kelp Recovery Project arose from a later collaboration of these organisations, alongside other national and local partners including the Blue Marine Foundation, Big Wave Productions, Sussex IFCA, Adur & Worthing Council, ZSL, University of Brighton, and UCL. The SKRP places great importance on engaging the local fishing community to harness their knowledge and encourage active participation in research.

SKRP also engages a community of over 50 organisations who form the SKRP Network, including citizen scientists who help collect data.

Finance

The research programme has received support from numerous funders, including the Postcode Planet Trust, where funds were raised by players of the People’s Postcode Lottery. Two community owned solar farms, Ferry Farm Community Solar and Meadow Blue Community Energy, also donated a percentage of their profits. Other notable contributors are the Pebble Trust, Barclays and Platform Earth through the Blue Marine Foundation, as well as corporate and personal donations through their website.

Monitoring and evaluation

With its strong focus on research and its assessment of both ecological and socio-economic outcomes, the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project provides a best-practice example of robust monitoring and evaluating of NbS.

To measure biodiversity, Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) cameras are deployed to record the presence and abundance of benthic species. This technique is supported by environmental (eDNA) sampling to account for camera-shy organisms. Other useful methods include acoustic surveys, population genetics, and crab and lobster surveys. To quantify socioeconomic outcomes, questionnaires were sent out to local fishers and community members to assess changes in their income and well-being as a result of the initiative.

The data SKRP collect can be used to evaluate the success of the legislation to ban trawling, and used to inform future interventions. The organisation plans to monitor the habitat “robustly and consistently” over many years to confidently report trends, provided they continue to receive adequate funding. Annual surveys over the next 5-10 years are needed to record how and at what rate kelp ecosystems recover from the impacts of trawling.

Trade-offs and limitations

While no trade-offs or limitations have been reported, some challenges encountered thus far are worth noting. First, significant increases in the extent and density of kelp are not anticipated for a few years, as recovery of such ecosystems can take years or even decades, even when key pressures have been removed from an area. Second, some aspects of the marine research and monitoring may inherently present more challenges to similar terrestrial research, such as due to accessibility issues. Also, it is difficult to measure the amount of kelp being buried in sediments and it is likely to be highly variable due to characteristics of local currents and seabed topography, resulting in high uncertainty over the value of kelp habitat as a carbon store. Lastly, there is a lack of previous research on kelp habitats, particularly those in the English channel. For example, most of the research to date on kelp as a blue carbon store has been based on the giant kelp species (Macrocystis pyrifera) found on the Pacific coast of North America which has very different characteristics to the species found in Sussex.

References

- Sussex Kelp Recovery Project: Progress & Impact Report 2021-2022. https://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Sussex-Kelp-Recovery-Project-Progress-Impact-Report-2021-2022.pdf

- Sussex Kelp. 2023. Webpage. https://sussexkelp.org.uk/

Intervention type

- Protection

- Restoration

Ecosystem type

- Coastal

- Temperate oceans

Climate change impacts addressed

- Other climate impact

- Storm surge

Instigators

- Local NGO or CBO (eg. indigenous)

- National conservation/environment organisation

- Research institutions

Societal challenges

- Biodiversity conservation

- Economic and Social development

- Food security

- Health

Outcomes

- Food security: Positive

- Water security: Not reported

- Health: Positive

- Local economics: Positive

- Livelihoods/goods/basic needs: Positive

- Energy security: Not reported

- Disaster risk reduction: Not reported

- Rights/empowerment/equality: Not reported

- Recreation: Positive

- Education: Positive

- Conflict and security: Positive

- No. developmental outcomes reported: 7

Resources

Read resource 1Read resource 2

Read resource 3

Read resource 4

Literature info

- Grey literature